Cyanide, a notorious poison from historical times, has caught attention owing to its extreme and expeditious action on living organisms. Is it a concern in the dairy industry? The answer is yes. Cyanide poisoning is one of the most common plant poisonings in cattle due to cyanide as cyanogenic glycosides in more than 1000s of plants, including many fodder crops. Cyanogenic glycosides, and chemically glycosides of α-hydroxynitrile are synthesized as secondary metabolites in plants.

Cyanide stored as glycosides in plants is released on physical disruption or damage when plant enzymes α-hydroxynitrile lyase and β-glycosidase come in contact with hydrolyzing glycoside to free cyanide/ hydrocyanic acid (HCN) and α-hydroxynitrile. This free cyanide gets rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream, blocks oxidative phosphorylation, and causes toxicity. Rumen microflora also breaks down cyanogenic glycosides to free cyanide. Cattle, buffalo, sheep, and goats are highly susceptible to cyanogenic glycoside toxicity.

It is surprising that, in India, the most common source of cyanide poisoning in cattle and buffalo is feeding young shoots of Sorghum vulgare and Sorghum sudanense (which are regularly used as fodder for livestock) after chopping. What makes the usually edible, highly nutritious; forage crops villains at certain times? The reasons are many. Certain factors increase the concentration of cyanogenic glycosides in plants.

| Plants | Cyanogenic glycoside |

| Bitter almond & Wild cherry | Amygdaline |

| Sorghum, Miller, Sudan grass | Dhurrin |

| Linseed, Velvet grass, Wild clover | Linamarin |

| Choke cherries, Service berries | Prunasin |

| Arrow grass | Triglochinin |

Factors affecting toxicity

Cyanogenic glycoside toxicity is commonly seen in ruminants, while monogastric animals are comparatively resistant owing to their acidic gastric pH. In addition, the rumen microbes contain enzymes that release cyanide from cyanogenic glycosides, resulting in the absorption of cyanide into the systemic circulation. Among ruminants, cattle are more susceptible than sheep.

Several plant factors like species, part of the plant, and environmental factors, also influence the toxicity in animals. For example, leaves contain the highest cyanide concentration compared to the shoot. Also, the young shoot is rich in cyanogenic glycosides compared to the mature parts of the plant. Therefore, grazing is riskier since the animals always prefer younger parts of the plant, while in stall feeding, the shoots will compensate for the high levels of HCN in leaves. HCN concentration is higher in drought-stricken, wilted, and when there are injuries to the plant. Plants resuming growth after a period of drought also contain high levels of HCN.

In ruminants, toxicity will be more if cyanogenic glycosides are consumed in a full stomach due to high levels of enzymes. The traveling stock and newly introduced are more susceptible, as they may not be accustomed to locally available plants. There is more chance of poisoning when the plant is fed in the morning compared to the evening. Ensiling the fodder reduces the HCN content in significant levels, while drying may not reduce the level.

How does cyanide cause toxicity?

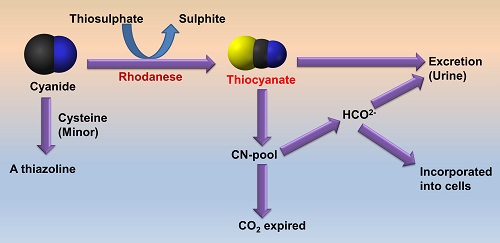

When released from cyanogenic glycosides in the rumen, cyanide gets rapidly absorbed into the systemic circulation and gets distributed throughout the body. The body has mechanisms to eliminate cyanide at lower levels. The primary detoxification mechanism is converting cyanide to thiocyanate; by the enzyme rhodanese, Thiocyanates get excreted in the urine. There are also minor metabolic pathways, like forming a thiazoline compound. Finally, some amount gets excreted via exhalation, giving the poisoned animal a bitter almond smell of breath.

Cyanide inhibits an enzyme cytochrome c oxidase inside the cells, essential for the cellular utilization of molecular oxygen for ATP synthesis in the mitochondria. This enzyme is a part of complex IV of the electron transport system. Due to this, cellular respiration is inhibited, and the oxygen delivered by arterial blood remains unutilized, giving the venous blood a bright red colour.

Due to the rapid action of cyanide, symptoms may be peracute or acute. It will depend on the level of cyanogenic glycosides present in the fodder and the amount consumed. Clinical signs include restlessness, laboured breathing, dyspnoea, salivation, mydriasis, and voiding of urine and faeces. The mucous membrane will be cherry red, turning cyanotic in terminal cases. Chronic toxicity has been reported, like sorghum cystitis ataxia syndrome of horses and cystitis ataxia syndromes in cattle, sheep, and goats. These neuropathic syndromes are associated with chronic low-level exposure to cyanogenic glycosides and low dietary sulfur. In addition, thiocyanate can act as a competitive inhibitor of thyroid follicular sodium-iodide symporter (NIS), resulting in hypothyroidism, goiter, and elevated TSH.

The veterinarian should wear appropriate protective equipment for a post-mortem examination of suspected cases, including respirators with cartridges. The venous blood will be cherry red but may turn brown when exposed to air. Blood clotting will be slower or may not occur. The rumen will be distended, and the contents may be evaluated by picrate paper test or rumen gas by Draeger cyanide gas detection tube. The samples to be collected include rumen contents, heparinized blood, feed, liver, and muscles. The specimens must be sealed in an air-tight container, labelled, refrigerated/frozen, and submitted without delay. If the facility to maintain the cold chain is unavailable, the samples can be preserved in 1-3 % mercuric chloride solution. Forage containing cyanide levels above 200ppm is considered to be toxic to ruminants. Estimation of urine thiocyanate level is also indicative of cyanide poisoning.

Treatment should not be delayed due to the rapid action of cyanide. Likewise, there should not be a delay to start therapy for diagnostic confirmation. Inhalation of amyl nitrite, followed by intravenous sodium nitrite, is recommended to induce methemoglobinemia since cyanide has an affinity to bind with the ferric ion in methemoglobin. In addition, intravenous sodium thiosulphate will hasten cyanide excretion by forming thiocyanate. Vitamin B12a (hydroxocobalamin) acts as a decoy receptor that binds with cyanide to readily excretable cyanocobalamin. Acidification of rumen contents with acetic acid mixed with cold water will reduce the release of cyanide from cyanogenic glycosides. Several new drugs like sulfanegen, DMAP (4-dimethyl-aminophenol), etc., are under clinical trials to treat cyanide toxicity.

How to prevent cyanogenic glycoside toxicity in ruminants?

For the prevention of any plant poisoning, the best way is to analyze the forage for the presence of any phytotoxins. Since the cyanogenic glycoside content is higher in young plants, do not feed your animals young Sorghum shoots less than 60cm tall. Also, avoid feeding wilted, drought-stressed, or frosted forage. Acclimatize the animal by gradually increasing the level of any particular forage instead of suddenly including a large quantity abruptly. Forages like Sorghum can be ensiled instead of fresh feeding to reduce the HCN content.

For further reading

- Gensa, U. (2019). Review on cyanide poisoning in ruminants. Synthesis, 9(6).

- Arnold, M., Gaskill, C., Smith, S., & Lacefield, G. D. (2014). Cyanide poisoning in ruminants. Agriculture and Natural Resources Publications. 168.

- Molossi, F. A., Ogliari, D., Melchioretto, E., Hugen, G. F. G., Quevedo, L. S., Vettori, J. M., & Gava, A. (2019). Experimental reproduction of cyanogenic poisoning by star grass (Cynodon nlemfuensis Vanderyst var. nlemfuensis cv.“Florico”) in cattle. Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira, 39, 238-243.

| The content of the articles are accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge. It is not meant to substitute for diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, prescription, or formal and individualized advice from a veterinary medical professional. Animals exhibiting signs and symptoms of distress should be seen by a veterinarian immediately. |

Be the first to comment