Abstract

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) is an economically devastating viral disease affecting the swine industry worldwide. It is caused by single-stranded RNA virus in the family Arteriviridae. For the past 20 years, PRRSV has remained the most costly disease affecting swine production worldwide because the high morbidity rate i.e 50–100 % with mortality rate of 20–100 %. Transmission occurs by the transfer of body fluids (excretions and secretions) through direct contact, ingestion, inhalation, coitus, and bite wounds or trans-placentally during gestation. Various clinical manifestation observe in infected pigs includes persistent high fever, red coloration of body, cyanopathy of ears, conjunctivitis, dyspnoea and severe diffuse pulmonary consolidation lesions. This manuscript includes clinical manifestation of PRRS in different age groups of pigs and their prevention and control strategies.

Introduction

The porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS or SRRP in Spanish) was clinically described for the first time in the USA in 1987 (Dial and Parsons, 1989), known by the name of mysterious porcine disease or blue ear disease, and lately it was clinically recognized in Canada and on 1990 in European countries (Dial et al.,1990). There were no clinical reports of the disease prior to 1987.Since 1987, the disease has spread rapidly and, coupled with the lack of scientific knowledge of PRRS, has caused alarm in the swine industry. The disease was spread fast almost worldwide. In 1991 the virus was isolated for the first time in The Netherlands and in The USA, followed by China on 1996 (Zhou et al., 2011). However, serological studies of stocked serum, takes back its origin to Canada in 1979 to USA and South Korea in 1985, been on the last one from imported animals to Japan from serum of outbreak reports and to Germany in 1988. Today the disease is found in almost all porcine producing countries and is endemic in most of them, with the exception of Australia, Sweden, Norway and New Caledonia which is the only countries reported as free of PRRS.

History of PRRS

In the late 1980s, reports of a disease of unknown aetiology began to accumulate in the United States, focusing initially on its clinical signs (Dial and Parsons, 1989). Veterinarians and researchers believed the syndrome to be unique because of its severity, its duration, its combination of reproductive and respiratory signs, and because no known swine pathogens could be implicated in most cases. Because the aetiology was unknown, the syndrome was given the name “Mystery Swine Disease (MSD)”. In retrospect, Mystery Swine Disease may have been an honest title for the syndrome, but the press often sensationalized the word “mystery, “which led to paranoia within the industry. By1990, clinical signs compatible with the disease were reported throughout North America wherever swine were intensively raised. In November1990, a syndrome similar to MSD was reported in Munster, Germany’? After the initial report in Germany, reports from other countries in Europe began to accumulate rapidly. As MSD spread throughout the world, so did names and acronyms describing the disease. Swine infertility and respiratory syndrome (SIRS) and MSD were used extensively in the United States. In Europe, common names included “porcine epidemic abortion and respiratory syndrome (PEARS),””porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS),”and “blue-eared pig disease” (Meredith, 1992). Participants of the 1992 International Symposium on the disease in St. Paul, Minnesota, agreed to use the European Commission name, PRRS (Collins, 1992). The International Office of Epizootics also recognizes PRRS.

The confusion surrounding the aetiology of PRRS was resolved in the summer of 1991.In June, Wensvoort et al. (1991) at the Central Veterinary Institute in the Netherlands reported that they had isolated a previously unrecognized virus from cases of PRRS. They named the new virus “Lelystadvirus,” after the town in which their research institute is located. They isolated the virus from 16 of 20 affected piglets and 41 of 63 sows, observed that 75%of 165affected sows seroconverted, and reproduced the clinical signs and recovered the virus in pregnant sows, their foetuses, and in growing piglets, all evidence implicating Lelystad virus as the cause of PRRS.

Aetiology

The PRRS virus is an enveloped RNA virus in the genus Arterivirus, classified in the virus family, Arteriviridae (Li et al., 2016). There is considerable heterogeneity in the genome of the PRRS virus because of inherent errors common in transcription of RNA. The prototype US virus is related to but distinct from the first European isolate (referred to as Lelystad virus) identified in the Netherlands. There are significant genetic and antigenic differences between these initial isolates. Genetic and antigenic variability between isolates, even within a country, remains a continuous challenge to control of the disease. The PRRS virus is only moderately resistant to environmental degradation. The virus is easily inactivated by phenol, formaldehyde, and most common disinfectants. The virus has a predilection for cells of the immune system, including pulmonary intravascular macrophages (PIM) and pulmonary alveolar macrophages (PAM); in the latter it replicates extensively. Primary PAMs and a limited number of continuous cell culture systems are used in isolating and maintaining virus. Strains of PRRS virus vary markedly in virulence. The basis for virulence differences is not yet known. Protective epitopes are not described nor can they be predicted from genomic analysis. The virus often appears to interact with other pathogenic viruses, bacteria and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae to magnify severity of diseases.

Susceptible species

Pigs of all ages are susceptible to PRRS, but in endemic farms young pigs manifest the disease the most. Although is still in debate, it has been proposed that some avian species are susceptible to infection, particularly ducks, which have been related to virus spread for weeks through their feces (Lunney et al., 2016).

Transmission

PRRSV is transmitted mechanically by direct contact with sick animals or with contaminated material by their saliva, urine, semen, mammary secretions, placental debris or feces; and most commonly by contaminated, static and apparently clean water(36), flies fed from infected animals and contaminated needles. Tran splacental transmission occurs to the implanted embryo, enabling the embryo transference, before the placental development (13 to 14th d of gestation) (Renukaradhya et al., 2015)

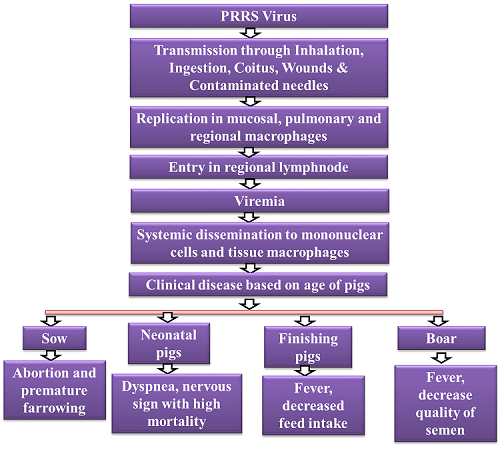

Pathology and pathogenesis

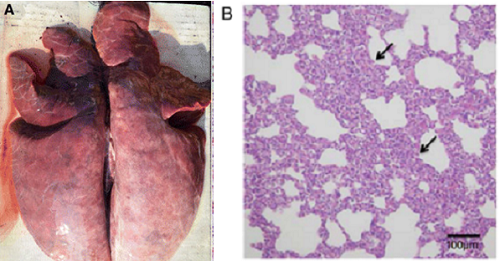

Piglets infected with PRRSV exhibited severe gross lesions with consolidation and haemorrhage (Fig. 2a). The parenchymas of the infected lungs were firm and heavy. Histopathologically it shows interstitial pneumonia with alveolar septa thickened by the infiltration of macrophages and lymphomononuclear cells (Fig. 2b). (Lunney et al., 2016)

Clinical signs

Breeding age gilts, sows, and boars

Clinical signs may include a period of anorexia, fever, lethargy, depression, and perhaps respiratory distress or vomiting. Mild cyanosis of the ears, abdomen and vulva has been reported in some outbreaks. Reproductive problems, often the most obvious signs, include a decrease in the number of dams that conceive or farrow. There is usually an increase in premature farrowings, late term abortions, stillborn or weak piglets and mummified fetuses. Preweaning mortality is high. Nursing pigs may have dyspnea (“thumping”). The period for reproductive signs varies with herd size but is usually two to three months in duration. A slow improvement in reproductive performance then begins. In larger operations, signs may be cyclical, especially if naïve gilts or sows continue to be introduced into the herd. There is evidence that subpopulations within large breeding herds escape initial infection but are infected when exposed later and serve as sources of continued virus shedding. Also, herds may be infected with multiple, heterologous strains of PRRS virus that are not completely cross-protective. In boars, clinical signs are similar to sows and are accompanied by a decrease in semen quality.

Young, growing and finishing pigs

Primary clinical signs among young pigs are fever, depression, lethargy, stunting due to systemic disease, and pneumonia. Sneezing, fever and lethargy are followed by expiratory dyspnea and stunting. Peak age for respiratory disease is four to ten weeks. Postweaning mortality often is markedly increased, especially with more virulent strains and the occurrence of ever-present concurrent and secondary infections. Older pigs, especially naïve, high-health swine, have similar respiratory signs. Heterologous infections may lead to prolonged or repeated outbreaks of respiratory disease.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is difficult because of the heterogeneity of the strains and the predisposition of acutely infected pigs to develop persistent infection (carriers) where the virus is difficult to detect because of low viremia and low viral titers in tissues (Williamson et al., 2018). The diagnosis is based on serology and besides of methods that determine the viral presence, such as detection of viral proteins or RNA, viral isolation, immunohistochemistry or reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR). Virus isolation requires 7-14 d, diagnostic samples are difficult to obtain and some field strains are difficult to isolate, all of this reduces the sensitivity of the test.

Differential diagnosis

Respiratory disease includes lesions or co-infections caused by influenza virus, Streptococcus suis, Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, Salmonella choleraesuis, Haemophilus parasuis, Pasteurella multocida, porcine circovirus, porcine respiratory coronavirus, and Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae are must taking into consideration before diagnose a case of PRRS.

Treatment of PRRS

There is no specific treatment for PRRS virus infection. Most treatments are intended to provide supportive therapy until the acute signs have subsided. Most strategies concentrate on preventing and treating secondary bacterial pathogens. Few treatment regimens have proven very effective, so it is often a challenge to maintain the morale of farm workers during an acute, severe outbreak. Although to prevent secondary bacterial infection antibiotics like tetracycline can be given to pigs.

Prevention and Control

- There is no single successful strategy for control of PRRS, largely because of virus variation, large swine populations, and unresolved issues of transmission. In some smaller herds, immunity may be sufficient so that infection is not causing significant economic losses, in which case no intervention is necessary. Often, there are sufficient losses to consider some or all of the following points for control. A control program should be tailored to fit the individual farm situation.

- An accurate diagnosis is essential to confirm the disease and epidemiology on a particular farm. This requires both disease characterization (demonstrate disease agents and lesions) and a serologic profile of pigs in the various stages of production. Serologic testing of a significant sample of animals from each stage of production should indicate the stage (acute or chronic) of infection in the herd as well where and how the virus is being spread in the herd. Once the disease is defined, a strategy can be developed to achieve one of two general goals, either to eliminate PRRS or to control (“live with”) PRRS.

- The goal of many herds is to “stabilize” the infection in the sow herd by assuring immunity in all breeding stock. This “herd immunity” prevents the reproductive failure and can decrease the likelihood of transmission of virus from dams to foetuses and offspring. When coupled with segregated rearing of offspring, clinical effects of infection can be minimized. Breeding herd stabilization can sometimes be accomplished by vaccination, intentional whole-herd infection, aggressive acclimatization of replacement breeding stock, or combinations of these strategies.

- Two major, generally recognized as essential, components are to limit the frequency of seed stock introductions to the sow herd and to assure that the replacement gilts be well-acclimatized to the PRRS virus present in the sow herd. Seed stock introductions to sow herds should not be more frequent than monthly, with quarterly or semi-annual introductions preferred. Assuring infection of replacement gilts, followed by at least 60 days recovery (cool-down) before they enter the sow herd is strongly recommended. Ideally, replacement gilts should originate from a single, PRRS-negative source and be infected only with the PRRS strain(s) present in a particular sow herd.

- Boars introduced into negative herds should be quarantined for 60-90 days after purchase and confirmed negative serologically. Those entering PRRS-positive herds require acclimatization to resident PRRS virus in a fashion similar to gilts. Many organizations that provide semen for artificial insemination now use PCR to assure that semen is free of PRRS virus.

- Sow herds and offspring that remain positive for PRRS may prefer to strive for minimizing clinical effect rather than trying to eradicate it and prevent re-infection. Acclimatization of breeding animals and management of pig flow allows for some success in “living with” PRRS. There are both killed and live commercial vaccines for control of reproductive and/or respiratory forms of PRRS that may be useful; experience suggests they are inconsistently efficacious. Autogenous killed PRRS vaccines have also been used with very limited success.

- Herds successfully “stabilized” for PRRS virus may produce PRRS-negative offspring. Once the breeding herd is producing PRRS-negative offspring, it is necessary to evaluate the nursery, grower and finisher phases. Initial testing should indicate whether it would be necessary to depopulate, clean and disinfect these stages. Nursery depopulation often improves production. All phases of production should use all in/all out management.

- Some sow herds that consistently produce negative offspring may attempt to eliminate PRRS from the sow herd. At that point, all subsequent replacement seed stock should be naïve for PRRS infection and any residual infected sows in the herd should be eliminated. The latter has been accomplished by testing (serology, PCR) and removal, or in some cases, by normal attrition.

- In some operations, it may be economically feasible to depopulate, clean and disinfect the facilities and, after a few weeks, repopulate with stock free of PRRS and other major diseases. Herd closure for at least 200 days has also been used as another means to stabilize a breeding herd without having to depopulate. Most breeding stock companies today provide PRRS-free seed stock which was once a major limitation. Before embarking on this strategy, one should honestly assess risk factors for re-infection of the herd as well as the level of biosecurity that can be maintained by the producer. Herds located in swine-dense areas are at great risk for re-infection.

- There is no specific treatment for PRRS. Broad-spectrum antibiotics may be useful in controlling secondary infections. Anti-inflammatory products (e.g. aspirin) are commonly administered during acute disease. Other helpful techniques include early weaning and isolation of piglets, various PRRS vaccination protocols, regular serologic monitoring, testing (ELISA, PCR and IFA) and removal of persistent carriers in herds with <10% infection, and improving biosecurity.

- Since the PRRS virus, the control strategies, and the specific farm situations are so variable, it is imperative that experienced practitioners, diagnosticians and research workers continue to objectively expand their knowledge to better control and eventually eliminate this financially devastating disease.

Vaccination

There are currently no licensed vaccines available for PRRS. Vaccine development is being pursued by several researchers and biologic companies at present, but we must remember the virus responsible for PRRS was isolated just 2 years ago. There are no published reports of vaccine trials to date. While the lack of publication is understandable, given today’s competitive biologics market, the absence of data for practitioners and producers has been frustrating. An efficacious vaccine may be produced; naturally infected sows develop immunity to rechallenge and an effective vaccine is available for the related Equine arteritis virus in horses.

Conclusion

PRRSV is a virus that remains a significant pathogen in swine and a challenge for management. Due to the complexity of the disease and multifaceted causes, diagnostics are important for determining the pathogens and affects.

References

- Li, Z., He, Y., Xu, X., Leng, X., Li, S., Wen, Y., Wang, F., Xia, M., Cheng, S. and Wu, H., 2016. Pathological and immunological characteristics of piglets infected experimentally with a HP-PRRSV TJ strain. BMC veterinary research, 12(1), pp.1-9.

- Lyoo, K.S., Yeom, M., Choi, J.Y., Park, J.H., Yoon, S.W. and Song, D., 2015. Unusual severe cases of type 1 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) infection in conventionally reared pigs in South Korea. BMC veterinary research, 11(1), pp.1-6.

- Williamson, S., Frossard, J.P. and Thomson, J.R., 2018. PRRS diagnoses in Great Britain 2016/17. The Veterinary Record, 182(5), pp.133-135.

- Dial, G. and Parsons, T., 1989, March. SMEDI-like syndrome (EMC?). In Proceedings of the American Association of Swine Practitioners (pp. 5-7).

- Dial, G.D., Hull, R.D., Olson, C.L., Hill, H.T. and Erickson, G.A., 1990. Mystery swine disease: Implications and needs of the North American swine industry. Prof Mystery Swine Dis Committee, pp.3-6.

- Zhou, Z., Ni, J., Cao, Z., Han, X., Xia, Y., Zi, Z., Ning, K., Liu, Q., Cai, L., Qiu, P. and Deng, X., 2011. The epidemic status and genetic diversity of 14 highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (HP-PRRSV) isolates from China in 2009. Veterinary microbiology, 150(3-4), pp.257-269.

- Meredith, M.J., 1992. Review of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome.

- Collins, J., 1992. Intenational symposium on SIRS/PRRS. Am Assoc Swine Pract Newsl, 4(4), p.1.

- Wensvoort, G., 1991. ‘Blue ear’disease of pigs. Veterinary Record (United Kingdom).

- Lunney, J.K., Fang, Y., Ladinig, A., Chen, N., Li, Y., Rowland, B. and Renukaradhya, G.J., 2016. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV): pathogenesis and interaction with the immune system. Annual review of animal biosciences, 4, pp.129-154.

- Renukaradhya, G.J., Meng, X.J., Calvert, J.G., Roof, M. and Lager, K.M., 2015. Live porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus vaccines: current status and future direction. Vaccine, 33(33), pp.4069-4080.

| The content of the articles are accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge. It is not meant to substitute for diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, prescription, or formal and individualized advice from a veterinary medical professional. Animals exhibiting signs and symptoms of distress should be seen by a veterinarian immediately. |

Be the first to comment