The hoof is an extremely important structure in bovine body. Cattle with a problem in hoof will eat less, which will reduce weight gain or milk production. Although some hoof problems are unavoidable, sound hoof management procedures can greatly reduce the incidence of hoof problems in all types of animals. A good hoof care program leads to lowered expenses in treatment of problems, as well as fewer losses due to decreased performance and productivity of the animal. In order to understand how to properly care for the hoof, it is important to understand the basic structure and anatomy of the hoof.

Anatomy of a bovine hoof

Cattle are cloven-footed animals and the hoof consists of two digits. The claws are named by their relative location on the foot. There is the outer, or lateral claw, and the inner, or medial claw. The space between the two claws is called the interdigital clef; the area of skin is called the interdigital skin. The different surfaces of the claws are named according to their relative position to the interdigital cleft: the abaxial surface is the outer wall of each claw, and the axial surface is the inner wall.

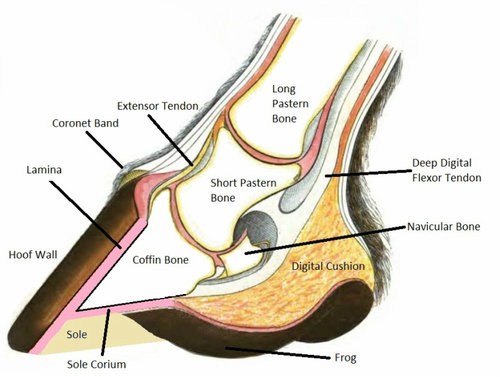

The hoof is described from the outside moving in, beginning with the hard outer covering of the hoof, known as the hoof wall, or horn (Figure 1). The horn is a hard surface, functionally like the epidermis of the skin. The cells that form the horn are produced by the tissue directly beneath the hoof wall, called the corium, at the hoof head. The corium is a nutrient-rich tissue that contains many important blood vessels and nerves inside the hoof. The corium continuously produces new cells that are then gradually pushed away from the quick. As the cells are pushed away from the corium, they die and produce the hard, new outer growth At this point the cells are said to have been keratinized, or cornified. The new growth comes out at the coronary band, the point where the hoof meets the hairy skin on the animal’s foot. The soft, new hoof growth that has just come to the surface is referred to as the perioplic horn and is shiny and holds in the moisture of the hoof. Bovine hooves grow about 1/5 to 1/4 of an inch per month.

Underneath the hoof is a slightly softer region, called the sole. The tissue that makes up the sole is produced by the corium of the sole, and is suppler than the horn of the hoof wall. The point where the hoof wall is bound to the sole is called the white line. The white line is a somewhat flexible junction between the sole and wall, allowing the hoof to be more flexible as the animal moves. The front region of the sole is called the toe, and the two bulbs at the opposite end of the foot are referred to as the heel bulbs. Inside the hoof, there are bones that play a key role not only in forming the shape of the hoof, but also in serving as a support structure for the leg and the rest of the body. The sole should be from five to seven millimeters thick for the inside of the hoof to be protected properly. Directly above the sole is the corium, which is below the digital cushion. The digital cushion is a pad of fatty tissue that serves to protect the corium, as well as to aid in blood transport in the leg. It also serves as a shock absorber for the digital phalange bones. The pedal bone is directly above the digital cushion and is the largest bone in the hoof. The pedal bones provide the framework for the general shape of each claw, and they are key components in the movement of the animal. The pedal bone is attached to the corium by sensitive connective tissue called the laminar tissue, or laminae. The laminae holds the animal suspended in its hoof. The deep flexor tendon is attached to the back portion of the pedal bone, making it very important for locomotion and flexion of the foot. The short pastern bones snugly fits into the top of the pedal bone, forming a condular joint referred to as the pedal joint. Seated directly behind the pedal joint is a small bone called the distal sesamoid bone (navicular bone), which serves as a fulcrum for the movement of the joint. The long pastern bone then fits into the top of the short pastern bone, forming the pastern joint. Above the long pastern bone is the fetlock joint and above that the cannon bone of the lower leg. The pedal bone is the only bone of these three that is completely inside the actual hoof, while the pastern bones serve to connect the hoof to the rest of the leg.

Common diseases

The majority of hoof diseases in the bovine species affect dairy cows. Aside from direct injury to the hoof, including punctures, ulcers, abscesses, and lacerations, laminitis is the most common non-infectious lameness in cattle. Laminitis can also cause many other problems in the hoof that otherwise would only occur from direct injury. Hairy heel warts and foot rot also produce large numbers of lame dairy cows each year.

Laminitis (inflammation of the laminar tissue) affects all ruminants. Laminitis itself is not nearly as detrimental as the side effects that it produces. Although laminitis will produce lame cattle, the other hoof problems that develop as side effects of laminitis are usually more severe. Laminitis in cattle results from dysfunction of the blood vessels serving the laminae and from softening of the ligaments of the suspensory apparatus leading to rotation of the pedal bone and compression of the digital cushion. This causes hemorrhages in the sole, as well as formation of lower quality horn in the hoof. When the bone begins to separate from the wall, it can cause the sole to separate from the wall at the white line, a disease known as white line disease. Laminitis can also lead to problems such as solar abscesses, and a condition known as under run heels, which results from the excessive overgrowth of the toe. Hairy heel warts/ interdigital dermatitis/ Papilomatous Interdigital Dermatitis is an infection that occurs mostly in dairy cows, producing inflamed, red lesions on the interdigital skin of the hoof. Hairy heel warts are thought to be caused by strains of the anaerobic bacteria Treponema. These bacteria thrive in muddy, dirty, and damp conditions. When foot warts are observed, the best way to treat them is with a footbath or a topical spray containing several remedies.

Hoof rot in cattle is caused by the bacteria Fusobacterium necophorum. These are anaerobic bacteria that thrive in muddy, damp conditions. Hoof rot can be characterized by a variety of symptoms. The animal will most likely exhibit some degree of lameness. Other symptoms may include a foul smelling discharge, reddened tissue above the hoof, and possibly swelling of the hoof and spreading of the toes. Treatment for hoof rot in dairy cattle consists of treatment with systemic antibiotics. Typically, copper sulfate is used in footbaths to harden the hoof and adjacent tissue, making it more difficult for bacterial infection to become established.

Maintenance

A well-maintained routine of cleaning and trimming of feet will lead to a far lower incidence of discomfort and lameness in the animals. Nutrition also plays a key role in hoof health and maintaining proper growth rate. By keeping an animal well fed with the proper nutrients such as zinc and biotin, it is much more likely that they will produce good-quality hoof horn and have stronger feet. Cattle do not require extensive trimming if the hoof remains balanced and wears down evenly on all walls of the hoof. However, it is a general recommendation that the hooves of dairy cows are checked and trimmed (if needed) twice a year. Regardless of whether or not an animal is shod, the animal needs to have its hooves cleaned regularly. Cleaning the hooves requires a tool called a hoof pick. It is used in a toe-to-heel action to dig out the matter that has built up on the sole, under the shoe, and especially in the clefts of the frog.

The hoof is a complex structure that plays a key role in many aspects of the overall health and productivity of animals. Healthy hooves lead to healthy animals, which raises productivity and income. When hooves are kept in good condition, it reduces the production losses that result from their discomfort and the costs in treating them. By maintaining a sound hoof management routine, animal owners can reduce their economic losses and increase their chances for profit in the future.

References

- Berry, Steven L. DVM, MPVM. Hoof Health. Western Dairy Management Conference, 1999; 14-17.

- Berry, Steven L. DVM, MPVM. The Three Phases of Bovine Laminitis. Hoof Trimmers Association, Inc. Newsletter, March 2002.

- Blowey, Roger. Cattle Lameness and Hoofcare and Illustrated Guide. IpswichUnited Kingdom: Farming Press Books, 1993.

- Burgi, Karl. Functional and Corrective Hoof Trimming. Comfort Hoof Care, July 2000.

- Greenough, Paul R., Laverne M. Schugel DVM, A. Bruce Johnson Ph.D., Zinpro Corporation’s Illustrated handbook on Cattle Lameness. USA: Zinpro Corporation, 1996.

- Roenfeldt, Shirley. How to judge a hoof trim. Dairy Herd Management, December 2000: 30-36.

- Schurg, William A. PhD What are Sole Bruises? Arizona Livestock Review Spring 2004:2.

- Toussant, Raven E DVM. Cattle Footcare and Claw Trimming. Ipswich,United Kingdom: Farming Press Books, 1989.

| The content of the articles are accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge. It is not meant to substitute for diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, prescription, or formal and individualized advice from a veterinary medical professional. Animals exhibiting signs and symptoms of distress should be seen by a veterinarian immediately. |

Be the first to comment