Background

The catastrophic pandemic of COVID-19 and the possibility of viruses originating from bats as well as other mammals has gained much attention and focused interests towards coronaviruses and the effect of their infections in other species of animals. Coronavirus can affect a wide variety of mammals and birds. Earlier, in humans, coronaviruses were (229E and OC43 Cov) commonly involved to cause mild respiratory diseases. On the contrary, it is one of the significant diseases of animals and poultry. Prior to the SARS epidemic (2003), coronavirus was not known to cause severe disease in humans. However, veterinarians have long experienced its potential for producing fatal diseases and epidemics in animals. There are numerous past instances relating to the emergence of new coronavirus strains from unknown reservoirs causing lethal infections within the naive animal flocks. As an example, a porcine epidemic diarrhea (PEDV) virus, genetically closely related to a human coronavirus 229E, which was responsible for severe diarrhea and widespread death in baby pigs from Asia (1980s) and Europe (1970s). Furthermore, recombination of animal coronaviruses may gain new genes that would cause alteration in host and tissue tropism. As an instance, Bovine coronavirus had acquired haemagglutinin from the influenza C virus which makes it capable to infect other species of animals. Similarly, target recombination of feline coronavirus and mouse coronavirus enable the former to infect mice. Therefore, it is necessary to know about different clinical syndromes occurring in animals due to coronaviruses. Bovine coronavirus is of significant importance, because it has high mutation and recombination rates, which may allow it to extend it’s pathogenicity and cross species barriers to adapt to new hosts. BCoV is a momentous infectious agent causing morbidity and mortality in bovines. Primarily, it is accountable for enteritis and diarrhea in calves and hemorrhagic enteritis (winter dysentery) in adults. At the same time, it is the principal agent responsible for bovine respiratory disease complex and pneumonia in cattle. Moreover, it’s been found to affect poults also. Genetically similar viruses are detected in canines and humans and thus, its zoonotic potential cannot be neglected. Hence in the present assert, author has described information about bovine coronavirus in brief.

The virus

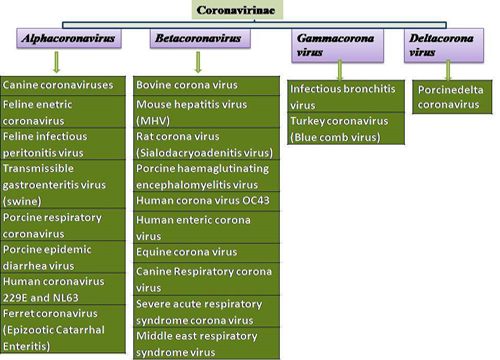

Bovine coronavirus (BCoV) is a single-stranded, non-segmented, positive-sense RNA virus, enveloped in glycoprotein with a genome size of 32 kb and a poly (A) tail. The virus is pleomorphic to spherical in shape and helical in symmetry with a diameter of about 120nm. It has club-shaped radial 20nm long surface projections that resemble a solar corona. Coronaviruses are classified into four different antigenic groups ie Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus. BCoV belongs to the genus Betacoronavirus within the family Coronaviridae, also including the closely related human respiratory pathogens SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV and HCoV-OC43. Various members of all genera affecting domestic animals are given in the following Figure.

The BCoV genome codes for five major structural proteins- the hemagglutinin esterase (HE) protein, the spike (S) glycoprotein, the small membrane (E) protein, the integral membrane glycoprotein (M), and the nucleocapsid (N) protein. The S and HE glycoprotein facilitate viral binding with the receptors on the host cells. Also, S glycoprotein mediates fusion with host cells and is accountable for the variations in the host range and tissue tropism of the coronaviruses. N phosphoprotein binds with the viral genomic RNA to form a helical nucleocapsid and is important in the replication of viral RNA. It is highly conserved among strains, so it is often the target for viral RNA detection assays.

Transmission

Fecal-oral and inhalation (contaminated droplets) are the principal portals of transmission of this virus. Contaminated feed and drinking water by the excretions from clinical cases or clinically normal carriers are the source of infection. The aerosol is the major route and is responsible for the rapid spread of BCoV within a herd causing outbreaks of pneumonia and upper respiratory diseases.

Pathogenesis

BCoV is a pneumoenterotrophic virus, which suggests it’s affinity to infect and replicates chiefly in the epithelium of the respiratory tract and the enterocytes of the intestinal tract in cattle. Initially, BCoV multiplies in the oropharynx of susceptible hosts and is then released in the lumen. As a result, a large quantity of the virus enters the gastrointestinal tract. Subsequently, the virus colonizes in the enterocytes of the upper duodenum and spreads caudally to other parts of the small intestine. It can affect the colon and parts of the large intestine producing lesions. In the intestine, the virus mostly replicates within the cytoplasm of matured enterocytes resulting in villi atrophy, sloughing and disruption of cell membranes. Disrupted surfaces of the intestine are covered by immature proliferated crypt epithelium having altered sodium transport across cells as well as less absorptive capability. Moreover, loss in disaccharidase enzyme progresses to the accumulation of lactose from milk within the lumen causing osmotic diarrhea. Furthermore, malabsorption is responsible for the loss of fluid and electrolytes resulting in dehydration and acidosis which will further progresses to circulatory failure and death. Excessive destruction of colonic cells followed by transudation of extracellular fluid and blood may occasionally lead to hemorrhagic diarrhea. BCoV is shed in the mucosal secretions and excretions of the upper respiratory and gastrointestinal tract respectively. In the upper respiratory tract, BCoV damages ciliated epithelial cells, which successively enhances the adhesion of commensals like Mannhemia hemolytica and Pasteurella multocida to the host cells. This results in pneumonia and sepsis.

Clinical Manifestation

BCoV is an etiology for three distinct clinical syndromes in cattle viz. calf diarrhea, hemorrhagic enterocolitis (winter dysentery) and respiratory infections. Coronavirus induced gastroenteritis can be notice in calves up to 3 months of age, however, disease is often fatal in calves under 3 weeks of age. It is characterized by profuse diarrhea; dehydration and acidosis, coinfection with rotavirus, E. coli, cryptosporidia and Salmonella spp. aggravate the condition of the affected animal. Diarrhea is occasionally seen mixed with blood and giving of an unpleasant odor. All age groups are vulnerable to the respiratory form of BCoV infection; however fatal pneumonia is often noticed in 2 to 6 month old calves. The clinical signs include nasolacrimal discharge, rhinitis, cough and fever; occasionally accompanied by diarrhea in both calves as well as adults. Concurrent secondary bacterial infections (Pasteurella spp., Mannheimia spp.) can worsen the condition and cause fatal bovine respiratory disease complex. Winter dysentery is a sporadic acute contagious hemorrhagic enterocolitis occurring in adult animals. It is characterized by hemorrhagic/watery and profuse diarrhea and is most prevalent during the winter months.

Pathology

BCoV causes acute gastroenteritis in neonates characterized by degeneration, necrosis and sloughing off of intestinal villous epithelial cells along with cells of the crypts. It leads to the stunting and fusion of villi, atrophy of the colonic ridges, petechiae leading to mal-digestion, mal-absorption and hemorrhages in the small and large intestines.

Winter dysentery generally occurs in a sporadic, an acute, or an epizootic fashion in a herd. The virus infection destroys epithelial cells of colonic crypts, leading to degeneration and necrosis of the crypt epithelium. Sloughing of damaged and necrotic epithelium can be seen grossly as massive quantities of frank, often clotted, blood within the spiral and distal colon of affected animals.

Pneumopathogenic BCoV is associated with epithelial degeneration and necrosis in the upper respiratory tract in addition to interstitial pneumonia in the lungs. There is subacute, exudative, fibrinous, and necrotizing lobar pneumonia with a moderate to severe degree of bronchitis and bronchiolitis in the affected animals. Bronchiolar epithelial necrosis is the typical lesion seen in BCoV-infected calves. Bronchiolar syncytia formation is also observed in feedlot calves suffering from this infection.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of BCoV is generally made using fecal samples where BCoV particles can be demonstrated by electron microscopy. Antigen capture ELISA is additionally readily used for the detection of BCoV in the nasal and intestinal tissues, secretions, and fecal samples. ELISA is widely used in seroprevalence studies for the detection of coronavirus antibodies. BCoV genome can be readily detected in nasal secretions and fecal samples by using RT-PCR, nested PCR, and real-time PCR with primers designed from the S gene and the highly conserved N gene.

Treatment and control

There is no specific cure for the coronavirus infection and animals are generally treated symptomatically. Coronavirus infection in young calves can be controlled by vaccinating the dam with a live vaccine or adjuvanted inactivated bovine coronavirus vaccine while she is pregnant. This provides instant passive immunity as colostrums and milk are dominated by IgG antibody from the serum and this passive immunity provides protection against coronavirus infections. This has been proved by detecting higher antibody titers in calves with relatively low incidences of pneumonia. Furthermore, intranasal vaccinations using a live-attenuated enteric coronavirus vaccine has been proposed to reduce the risk of bovine respiratory disease complex (‘shipping fever’) in cattle. To reduce disease incidences, additional managemental care is needed ensuring an adequate supply of colostrum to newborn calves as well as following appropriate methods of hygiene and housing ventilation maintenance.

|

The content of the articles are accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge. It is not meant to substitute for diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, prescription, or formal and individualized advice from a veterinary medical professional. Animals exhibiting signs and symptoms of distress should be seen by a veterinarian immediately. |

Informative and very well framed, will be useful for Veterinarians.

Really informative..it can help to create awareness among the society

Very nice information to all veterinarian..

खूप छान इंफॉर्मशन !!!!!

Excellent, very informative and useful

Nicely composed and very well-drafted. Recommended for all the livestock farmers..

Nicely composed and very well-drafted. Recommemded for all the livestock farmers..

Reliable and authentic in brief information about latest virus

Very use full information Dr

Very useful information

Yeah, It is just a step to create awareness about animal diseases

Thanks Dr Uday

Very informative, will help to create awareness among society

Very Informative

Learning from the current event it is must to pay attention to animal related disease..