Abstract

Kyasanur forest disease (KFD) is rare but very important disease of non- human primates, due to its zoonotic nature. KFD is acute, febrile, hemorrhagic disease of monkeys and human, mainly in the people living near forest area. It is caused by Flavivirus an hard tick Haemaphysalis spinigera plays fundamental role in transmission of a disease. Generally subacute type of infection occurs and disease can be identified by clinical signs (high fever, gastrointestinal, neurological and hemorrhagic manifestations), and lesions. Confirmatory diagnosis is made on the basis of Hematology, various serological techniques like ELISA, IFA, CFT, HI, RT-PCR, virus inoculation. Biosecurity measures, immunization, vector control and recent advances like One Health Approach are the key to control this disease. Key words: Kyasanur Forest disease, monkey fever, an overview. The disease was first reported from Kyasanur Forest in Sagar and Sorab Taluka’s of the Shimoga district, Karnataka state, in India in March 1957 and was first manifested as an epizootic outbreak among monkeys.

Introduction

- KFD is a rare, re-emerging tick born viral hemorrhagic disease of non- human primates such as macaques, monkeys, baboons, marmosets, etc.

- It causes acute, febrile illness in human and monkeys.

- It is of zoonotic importance & can be fatal to humans and other primates.

Reality bites

- Literature searched did not reveal much information on this disease outbreaks in monkeys & human beings both in India & abroad.

- As on today KFD is found to be enzootic in certain pockets of Karnataka state only. However, it is likely that the outbreaks may be seen in other forests of India.

- It is also observed that there are meagre studies on this disease outbreaks in human being.

- KFD is noted only in monkeys & some primates, but the detail studies of those outbreaks could not be tressed out.

- This information may create interest in the scientist handling this disease & may throw some light in future. Also This is a hand-out as a “Ready to refer information” for field veterinarians handling wild life diseases & their management.

Epidemiology

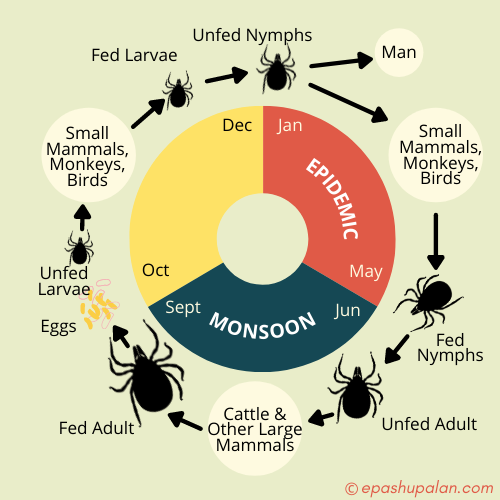

- High mortality of monkeys was generally observed from December to May which coincided with the seasonal activity of immature stages of Haemaphysalis ticks, the incriminated vectors of KFDV (Pattnaik, 2006).

- Annual incidence in India of 400–500 cases (Holbrook, 2012).

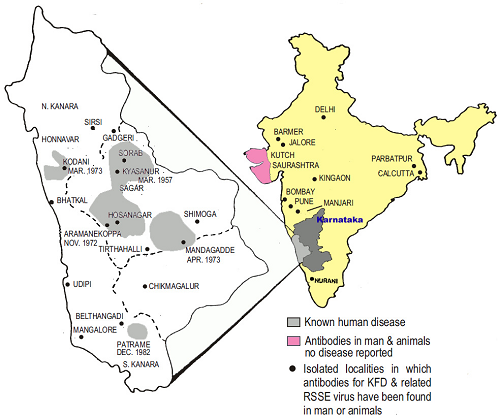

In India

- KFDV was first isolated from sick and dying monkeys in the Kyasanur Forest in 1957.

- The virus has been detected in monkeys in parts of Bandipur National Park (Chamarajnagar) and parts of the Nilgiris. Human infection occurred in Bandipur through handling of dead monkeys that were infected. A human carrier was also detected in Wayanad, Kerala (Mourya, et al, 2013).

- The disease has shown its presence in the adjacent states of Karnataka including Kerala, Maharashtra, Goa, Tamil Nadu and Gujarat (Awate, et al, 2016).

- Other than Karnataka state, the primary site of introduction of KFDV, antibodies against KFDV have also been detected in humans in several parts of Kutch and Saurashtra of Gujrat state (semi-arid area, around 1200 km away from main focus of KFD) and isolated localities like Ramtek (near Nagpur), Kingaon and Parbatpur of West Bengal state of India.

- A recent serological survey, conducted among the human population of the Andaman and Nicobar islands of India, reported the highest prevalence of HI (hemagglutination inhibition) antibodies against KFDV (Pattnaik, 2006).

- During the initial outbreak, in year 2003 there were 466 human cases and 181 more in the following year.

- It has caused epidemic outbreaks of hemorrhagic fever affecting 100 to 500 people per year since then.

Human cases & monkey deaths during 1957-2004

| Taluk | Human Cases | Monkey deaths |

| Sorab | 2761 | 2321 |

| Sagar | 3512 | 319 |

| Hosnagar | 3683 | 592 |

| Thirthahalli | 6786 | 399 |

| Sirsi | 239 | 64 |

| N.R. Pura | 1050 | 58 |

| Koppa | 772 | 68 |

| Belthangdi | 1092 | 324 |

| Other areas | 4826 | 2330 |

| Total | 24721 | 6475 |

Global epidemiology

- KFDV has also been isolated in Saudi Arabia and the People’s Republic of China.

- One of the variants of KFDV was isolated from the patients of hemorrhagic fever during 1994 and 1995 in the Makkah region of Saudi Arabia referred to as the Alkhurma variant or subgroup.

- In 1989, a related virus was isolated from a febrile patient in Nanjian County in the Hengduan Mountain region of Yunnan Province in southwestern China; initially it was referred to as Nanjianyin virus, but now it is considered as a strain of KFDV.

- Now, KFD is only reported from India (National centre for disease control, Delhi).

Reported occurrence of KFD virus in recent years in India

2012 100 confirmed cases in Karnataka; tick and monkey positivity

2012 KFDV confirmed in monkey specimen in Nilgiri, Tamil Nadu

2012– 13 Outbreak in the Bandipur National Tiger Reserve, Karnataka; confirmed by human and monkey positivity

2013 Human case confirmed in Wayanad, Kerala

2014 Outbreak in seven health centers in Thirthahalli, Shimoga, Karnataka

2014 Human case confirmed in Wayanad, Kerala

2014 Outbreak in a tribal population, Malappuram, Kerala

2014 Anti-KFD IgG antibody positivity in a tribal population of the Palakkad and Wayand districts, Kerala

2015 Confirmed in monkey specimen in Nilambur, Malappuram, Kerala

2015 Tick positivity for KFDV in Wayanad, Kerala

2015 Outbreak in Wayanad, Kerala [18 confirmed cases; Pulpally (7), Mullankolly (8), Chethayalayam (1), and Poothadi (2)]

2015 Outbreak in Shimoga, Karnataka [35 confirmed cases]

2015 Outbreak in Pali village, Sattari Taluka, northeast Goa [18 confirmed cases]

Etiology

- KFD is caused by a Flavivirus (Arbovirus) of Flaviviridae family.

- It is a spherical, enveloped, single stranded, positive sense RNA virus.

- Have icosahedral geometries with a pseudo-T=3 symmetry

- Generally labile, being sensitive to heat, detergents and organic solvents like benzene, chloroform, ether, ketones, phenol, toluene, etc. (The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)

- Figure- Flavivirus structure (Rossmann, 2019)

Transmission

- Reservoir hosts for KFD are porcupines, rats, squirrels, mice, shrews, etc.

- The vector for disease transmission is Hard tick i.e. Haemaphysalis spinigera (Forest tick).

- Bonnet macaque are very susceptible.

- Monkeys are amplifying hosts.

- Heavy mortality in Langur & Red-faced bonnet monkeys has been noted.

- Man & cattle are incidental host & man acts as terminal host (no human-human transmission)

- Large animals such as goats, cows, and sheep may become infected with KFD but play a limited role in the transmission of the disease.

- Human get infection from bite of nymphal stages of three host tick H. Spinigera.

Life cycle of the tick (Haemaphysalis spinigera)

IP, Case fatality rate

- Incubation period- 3-8 days (sub-acute type of infection)

- Case fatality rate- 2-10 % (lower than Alkhurma virus infection i.e. 25% as stated by Pattnaik, 2006).

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis of KFD has been prepared in a schematic manner for better understanding of the disease.

Stages of disease

This disease show biphasic illness, which can be divided into 4 stages:

- Stage I (Initial prodromal stage) – starts with a sudden onset of fever and severe head-ache, hypotension and hepatomegaly, sore throat, diarrhea and vomiting, anorexia, insomnia, severe pain in the lower and upper extremities, and prostration.

- Stage II – This is characterized by hemorrhagic complications & neurological manifestations such as mental confusion, tremors, and abnormal reflexes; and bronchopneumonia or development of coma, which may occur in few cases prior to death.

- Stage III & Stage IV – It is a stage of recovery.

Clinical signs & Symptoms: In Human

- High fever 104 ° F (40 ° C) with frontal headache

- Chills (The feeling of being cold, though not necessarily in a cold environment, often accompanied by shivering or shaking).

- Bradycardia.

- Conjunctivitis.

- Severe skeletal muscle pain.

- Gastrointestinal symptoms – This includes vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhoea.

- Bleeding in the gum, nose (epistasis), cough (hemoptysis), gastrointestinal bleeding resulting in dark feces (melena), and discharge of fresh blood in the stools

- Other symptoms includes muscle stiffness, tremors, absence of reflexes and mental disturbances.

- Some patients may develop coma or bronchopneumonia prior to death.

Gross lesions

Significant gross lesions noted are,

- Some cases shows haemorrhagic pneumonia.

- Focal necrosis of liver.

- In fatal cases, aseptic meningitis, abnormalities of CSF.

- In few cases cerebral oedema.

Microscopic lesions: in animals

- Predominance & flooding of macrophages and lymphocytes in liver, spleen and kidney with tubular damage in kidney.

- A moderate to marked prominence of the reticuloendothelial elements in the liver and spleen with marked erythrophagocytosis and inflammatory cells in brain tissue are the microscopic lesions recorded.

In Human

- Parenchymal degeneration of the liver and kidney, haemorrhagic pneumonitis.

- Moderate to marked prominence of the reticuloendothelial elements in the liver and spleen, with marked erythrophagocytosis are recorded.

Diagnosis

(Samples collected for diagnosis: Serum, monkey viscera & tick.)

- On the basis of Signs & symptoms – High fever, haemorrhagic & neurological symptoms.

- Haematology – Leukopenia is a constant feature in KFD patients and was due to a reduction in both neutrophils and lymphocytes (Pattnaik, 2006).

- Serology – Isolation of KFD Virus from patient’s serum

- Demonstration of anti-KFD antibodies – using Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA). Presence of immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies in serum and in cerebrospinal fluid (CS) are indicative of acute infection.

- Demonstration of virus -The virus can also be diagnosed by complement fixation (CFT) and hemagglutination inhibition (HI) tests.

- Virus inoculation – The virus can easily be isolated by intracerebral inoculation into infant or adult mice.

- By RT-PCR – It was found to be more sensitive and can detect a very low copy number of KFD viral RNA (38 copies as stated by Mourya, 2012)

Differential diagnosis

The KFD must be differentiated from similar type of diseases such as

- Meningococcemia in human – hallmark sign of meningococcemia is a rash that does not fade under pressure which is not seen in KFD.

- Measles in human – blotchy skin rashes & sore throat differentiate this from KFD.

- Enteroviral infection- include fever, headache, respiratory illness, and sore throat and sometimes mouth sores or a rash which differentiate it from KFD.

- Dengue fever – high fever, headache, muscle pain same like KFD but rashes also seen which distinguish one from other.

- Drug eruption- appear as a variety of skin rashes, including pink to red bumps, hives, blisters, red patches, pustules, or sensitivity to sunlight, all these symptoms not seen in KFD

- Secondary syphilis in human – characterised by rash which is not seen in KFD

- Gonococcemia in human- characterized by a hemorrhagic vesiculopustular eruption, bouts of fever are similar to KFD and arthralgia or actual arthritis of one or several joints differs it from KFD.

Prevention & Control

- KFDV is one of the highest-risk category pathogens designated as a Biosafety Level-4 pathogen.

- It is also considered as one of the potential bioterrorist weapons, which requires timely control to decrease the mortality and morbidity so observed.

- Prophylaxis by vaccination- inactivated chick embryo fibroblast tissue culture vaccine is used. Two doses of vaccine are administered to individuals aged 7-65 years at an interval of one month followed by periodic boosters after 6-9 months (ICMR, 2020).

- Protective clothing & use of repellents like DEET (N, N-Diethyl-3-methylbenzamide), dimethyl phthalate, benzyl benzoate, dimethyl carbamate, and indalone.

Physical control

- Controlled burning of the dry leaves and bushes in the forest boundaries, premises of human habitats.

- Use of gum boots/ shoes while entering in forest area.

• Tick control

- Reduce breeding sites using flame gun or insecticides containing Cypermethrin (10% w/v), Deltamethrin (1.25% w/v), Flumethrin (1% w/v), Permethrin (1% w/v), fenvalerate (20% w/v). (B.B. Bhatia)

- Spray insecticide in cracks & crevices.

- Use of insect repellents.

- Remove attached ticks immediately.

One Health Approach

- Now a days this plays very important role in case of zoonotic diseases.

- One health Initiative has a great role to play in maintaining balance between man-animal-environment interface.

- The COHEART centre situated in a strategically advantageous area can collaborate with centre for KFD surveillance among wildlife, domestic animals, tick incrimination and thereby identification of hotspots and also track the geographical expansion of the virus. (Sukumaran and Pradeepkumar, 2015)

Acknowledgment

Author is thankful to the Associate Dean, COVAS, Parbhani for providing facilities. Also Sutherland is thankful to Dr. V.V. Deshmukh, Professor and Head, Department of Veterinary Public Health of this college for help rendered and encouraging to write this manuscript.

References

- Priyabrata Pattnaik, 2016 Kyasanur forest disease: an epidemiological view in India Published online in Wiley InterScience, 16: 151–165.

- Syed Z. Shah1, Basit Jabbar, Nadeem Ahmed, Anum Rehman, Hira Nasir, Sarooj Nadeem, Iqra Jabbar , Zia ur Rahman and Shafiq Azam, 2018 Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Control of a Tick-Borne Disease- Kyasanur Forest Disease:Current Status and Future Directions Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, Volume 8 | Article 149

- https://vaccine.icmr.org.in/kfd (ICMR,2020)

- Devendra T. Mourya, Pragya D. Yadav, V, K. Sandhya, and Shivanna Reddy, 2013 Emerg Infect Dis.; 19(9): 1540–1541.

- P. Awate, P. Yadav, D. Patil, G. SapkalY, GuravD, T. Mourya, 2016 Outbreak of Kyasanur Forest disease (monkey fever, ) in Sindhudurg, Maharashtra State, India, 2016, Letter to the Editor, 72(6) : 759-761.

- John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Rev. Med. Virol. 2006; 16: 151–165

- M. Rossmann, 2019 Virus Taxonomy: 2019 Release, EC 51, Berlin, Germany, July, 2019 ICTV (The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses) report on virus classification

- B.B. Bhatia, K.M.L. Pathak and P.D. Juyal (2016), textbook of veterinary parasitology, Kalyani publishers, page no. 396.

- The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Ashok Munivenkatappa, Rima Rakesh Sahay, Pragya D. Yadav, Rajalakshmi Viswanathan, and Devendra T. Mourya, 2018 Indian J. Med. Res., 148(2): 145–150. (doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_688_17).

- Devendra T.Mourya, Pragya D.Yadav, RajeevMehla, Pradip V.Barde, Prasanna N.Yergolkar, Sandeep R.P.Kumar, Jyotsna P.Thakare, Akhilesh C.Mishra, 2012 Diagnosis of Kyasanur forest disease by nested RT-PCR, real-time RT-PCR and IgM capture ELISA, (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.07.019).

- Michel R. Holbrook, 2012 Kyasanur forest disease , Antiviral Research, 96(2) : 353-362, (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.10.005).

- Sukumaran A, Pradeepkumar AS. 2015 One Health approach: A platform for intervention in emerging public health challenges of Kerala state. Int. J. One Health, 1:14-25.

- Patil, D.R., Yadav, P.D., Shete, A. 2020 Study of Kyasanur forest disease viremia, antibody kinetics, and virus infection in target organs of Macaca radiata. Sci Rep., 10, 12561 (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67599)

- A.T. Sherikar, V.N. Bachhil, D.C. Thapliyal (2004), Textbook of Elements of Veterinary Public Health, ICAR, 4th Reprint, pp 313-315.

- P.J. Quinn, B.K. Markey, W.J. Donnelly and F.C. Leonard (2001), Veterinary Microbiology and Microbial Disease, Wiley- Blackwell, 2nd Edition, pp 425.

Be the first to comment