Abstract

Lumpy skin disease (LSD) is a viral disease of cattle and buffalo caused by Capripox virus of family Poxviridae. It is emerging threat to cattle industry mainly causing nodules all over the body. LSD is an acute, subacute or inapparent viral disease characterized by pyrexia, localized or generalized skin pox lesions and generalized lymphadenopathy. The disease originated from Africa, but it has spread to countries of the Middle East and poses a serious threat to Europe and Asia. In india the disease was first reported in Odisha in august 2019. LSD has been discovered in North-Eastern states likes Manipur, Assam, Arunachal Pradesh earlier. Thereafter the outbreaks were also reported in Andra Pradesh, Karnataka and Telangana. Recently in 2020, Vidarbha, Marathwada, Gadchiroli and Beed districts of Maharashtra were severely affected with LSD. Sources of transmission of lumpy skin disease are cutaneous lesions and crusts. Agro-climates, communal grazing, biting-fly, and introduction of new animals are associated with the occurrence of lumpy skin disease. It is enzootic in Africa, mainly a disease of cattle with 20% morbidity and 2% case fatality. It is economically devastating viral diseases which cause several financial problems in livestock industries as a result of significant milk yield loss, infertility, abortion, trade limitation and sometimes death in most African countries including Ethiopia. Diagnosis of LSD is based on clinical signs, virus isolation, histopathology and serological methods. Since LSD is a viral disease, there is no specific treatment for this disease.

Introduction

Lumpy skin disease (LSD) is re-emerging or transboundary viral disease of cattle caused by LSD virus (LSDV) of the family Poxviridae characterized by skin nodules presents all over the body (Neamat-Allah et al., 2015). Lumpy skin disease virus (LSDV) is a virus from the family Poxviridae, genus Capripoxvirus. The two other virus types in this genus are Sheeppox virus and Goatpox virus (Sudhakar et al., 2020). Due to its rapid spread and extreme economic losses, such as decreased milk production and weight gain, mastitis, infertility, and death, the OIE has classified this disease as “List A.”. Incubation period of LSD is 7-14 days in experimental infections and 1-4 weeks in natural outbreaks. Morbidity and Mortality rate is varies between 10-20% and 1-5% respectively (Shalaby et al., 2016)

Synonyms: Pseudo-urticaria, Neethling virus disease, exanthema nodularis bovis, and knopvelsiekt.

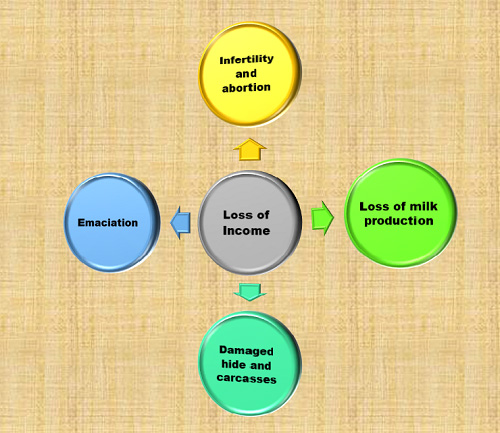

Economic Impact

Epidemiology

LSD is endemic in most African countries. LSD has been reported in most countries in Africa, the Middle East including Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Iran, Iraq, and Turkey, and Central Asia (Şevik et al., 2016). In india the disease was first reported in odisha in august 2019. LSD has been discovered in North-Eastern states likes Manipur, Assam, Arunachal Pradesh earlier. Thereafter the outbreaks were also reported in Andra Pradesh, Karnataka and Telangana. Recently in 2020, Vidarbha, Marathwada, Gadchiroli and Breed districts of Maharashtra were severly affected with LSD.

Host Susceptibility

LSDV is highly host specific and causes diseases mainly in cattle (Bos indicus and B. taurus) and water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis).

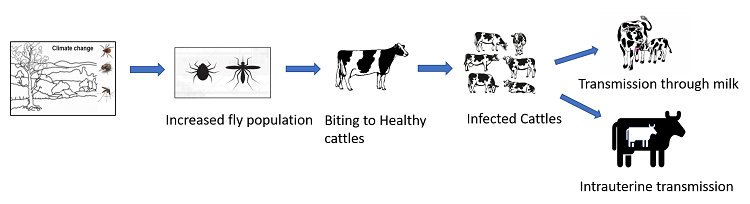

Transmission cycle

Pathogenesis

Biting of fly to healthy animals

![]()

Viremia developement

![]()

Viremia developement

![]()

Localisation in the skin and development of inflammatory nodules

![]()

Spreding of virus at secondary sites of infection by monocytes

![]()

Keratinocytes tropism of LSDV; Hyperplasia and ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes

![]()

Formation of epidermal microvescicles; inflammatory cells infiltration into dermis

![]()

Coalescence of epidermal microvescicles into large vescicles and ulceration develops

Clinical sign and Pathology

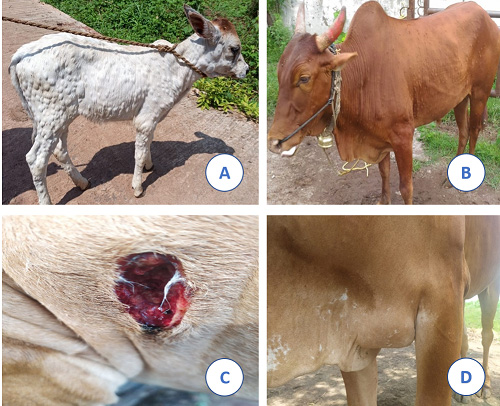

The first clinical sign in LSD infected animals will be fever that may exceed 41°C followed by rhinitis, conjunctivitis and excessive salivation, depression, anorexia and emaciation. The superficial lymph nodes will be enlarged. Skin nodules of 2–5 cm in diameter develop, particularly on the head, neck, limbs, udder, genitalia and perineum within 48 hours of onset of the febrile reaction. The skin, subcutaneous tissue, and often even the underlying muscles are all involved in these nodules, which are circumscribed, firm, round, and elevated. Large nodules may become necrotic and gradually fibrotic and persist for several months (“sitfasts”); the scars may remain indefinitely. Small nodules can resolve on their own without any consequences. Myiasis of the nodules may occur. Vesicles, erosions and ulcers may develop in the mucous membranes of the mouth and alimentary tract as well as in the trachea and lungs. Limbs and other ventral parts of the body, such as the dewlap, brisket, scrotum and vulva, may be oedematous, causing the animal to be reluctant to move. Bulls may become permanently or temporarily infertile. Abortion may occur in pregnant cows and be in anoestrus for some months. Recovery from severe infection is slow due to emaciation, mastitis, secondary pneumonia, and necrotic skin plugs, which are subject to fly strike and shed leaving deep holes in the hide (Fig. 3).

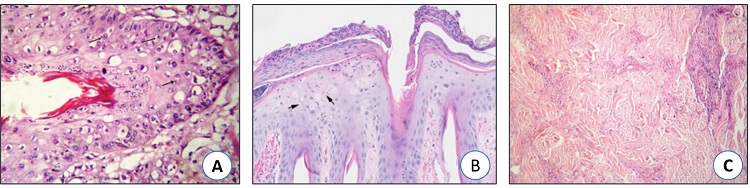

Histopathology

Histologically there is mild acanthosis, ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes with intracytoplasmic intracellular inclusion bodies, histiocytic inflammation of the dermis and fibrinonecrotic vasculitis (Fig. 4).

Diagnosis

LSDV is routinely diagnosed based on case history, clinical signs, gross and histopathological findings but more accurately by using molecular technique like PCR. A confirmed diagnosis is based on transmission electron microscopic (TEM), immunoperoxidase (IMP) staining, antigentrapping enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test (Al-Salihi et al., 2014). In serological test, Virus neutralisation is the gold standard test for the detection of antibodies raised against capripoxviruses. Capripoxvirus antibody enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay: new commercial kits for detection of capripoxvirus antibodies are currently being developed and released on to the market.

Differential Diagnosis

Severe LSD is highly characteristic, but milder forms can be confused with the bovine herpes mammillitis, Bovine papular stomatitis, Pseudocowpox, Orthopoxviruses, Dermatophilosis, Demodicosis, Insect or tick bites, Besnoitiosis, Rinderpest, Hypoderma bovis infection, Photosensitisation, Urticaria, Cutaneous tuberculosis and Onchocercosis.

Treatment

Since LSD is a viral disease, there is no specific treatment for this disease. However, treatment of affected animals by administration of antibiotics (Dicrysticin, OTC, Enrofloxacin) to prevent secondary bacterial infections and NSAID medicines has been practiced with supportive therapy (B-complex, Dextrose saline and Immunomodulator) for 5–7 days, which may be useful to reduce the severity of the disease. Treatment and management of clinical cases of LSD or in the event of outbreaks in cattle and buffalo are necessary to minimize the economic losses to farmers.

Prevention and Control

The current LSD outbreak in Europe and Western Asia has revealed that early identification of the index case, accompanied by a rapid and widespread vaccination campaign, is essential for effective control and eradication of LSD. Using statistical modelling, the effectiveness of complete stamping-out (killing both clinically affected cattle and unaffected herd-mates) and selective stamping-out (killing only clinically affected cattle) policies were compared. The researchers discovered that complete stamping-out and partial stamping-out had equal chances of eradicating the infection. The study also emphasized the importance of starting vaccination program before the virus makes an appearance. Control and management of fly population play significant role in prevention of LSD outbreaks.

Sanitary prophylaxis

- Free countries: Import limits on domestic cattle and water buffaloes, as well as some animal products. Surveillance for LSD should be carried out at least 20 kilometres away from an infected country or region.

- Infected countries: Control of LSD depends on restriction of movement of cattle in infected regions, removal of clinically affected animals, and vaccination. Movement restrictions and removal of affected animals alone without vaccination are usually not effective. Proper disposal of dead animals (e.g. incineration), and cleaning and disinfection of premises and implements are recommended for LSD. There is currently no evidence of the efficacy of vector control in preventing disease. See OIE Terrestrial Animal Health Code for regulations covering the recovery of LSD-free status of a country or zone.

Medical prophylaxis

LSD can be prevented by vaccination with a live-attenuated CPPV strain. The most commonly used vaccine for LSD is the “Homologous” LSDV live attenuated vaccine strain for example “Neethling” LSD strain. Other is “Heterologous” sheeppox or goatpox virus live attenuated vaccine strain. Following vaccination with live or attenuated capripox virus, a local reaction at the site of inoculation as well as fever and a decrease in milk yield may occur. There are currently no commercially available new generation recombinant capripox vaccines.

Conclusion

The farmers are continuously facing the emerging diseases outbreaks in cattle industry which cause huge economic losses to farm production. LSD is one of the emerging problems for farmers to overcome farm losses. The disease was observed to be more serious in young animals and causing mortality. A trend of seasonality was also observed in its occurrence. Eradication of the disease is the ultimate and optimal goal when it is reported in a new country. Regular deworming and vaccination remains the most manageable and realistic protocol to control LSD. Management and maintenance of farm is also playing significant role in preventing LSD in farm animals.

References

- Alkhamis, M.A. and VanderWaal, K., 2016. Spatial and temporal epidemiology of lumpy skin disease in the Middle East, 2012–2015. Frontiers in veterinary science, 3, p.19.

- Al-Salihi, K., 2014. Lumpy skin disease: Review of literature. Mirror of research in veterinary sciences and animals, 3(3), pp.6-23.

- EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare (AHAW), 2015. Scientific Opinion on lumpy skin disease. EFSA Journal, 13(1), p.3986.

- Gari, G., Bonnet, P., Roger, F. and Waret-Szkuta, A., 2011. Epidemiological aspects and financial impact of lumpy skin disease in Ethiopia. Preventive veterinary medicine, 102(4), pp.274-283.

- Neamat-Allah, A.N., 2015. Immunological, hematological, biochemical, and histopathological studies on cows naturally infected with lumpy skin disease. Veterinary world, 8(9), p.1131.

- Ochwo, S., VanderWaal, K., Munsey, A., Nkamwesiga, J., Ndekezi, C., Auma, E. and Mwiine, F.N., 2019. Seroprevalence and risk factors for lumpy skin disease virus seropositivity in cattle in Uganda. BMC veterinary research, 15(1), pp.1-9.

- Şevik, M., Avci, O., Doğan, M. and İnce, Ö.B., 2016. Serum biochemistry of lumpy skin disease virus-infected cattle. BioMed research international, 2016.

- Shalaby, M.A., El-Deeb, A., El-Tholoth, M., Hoffmann, D., Czerny, C.P., Hufert, F.T., Weidmann, M. and Abd El Wahed, A., 2016. Recombinase polymerase amplification assay for rapid detection of lumpy skin disease virus. BMC veterinary research, 12(1), pp.1-6.

- Sudhakar, S.B., Mishra, N., Kalaiyarasu, S., Jhade, S.K., Hemadri, D., Sood, R., Bal, G.C., Nayak, M.K., Pradhan, S.K. and Singh, V.P., 2020. Lumpy skin disease (LSD) outbreaks in cattle in Odisha state, India in August 2019: Epidemiological features and molecular studies. Transboundary and emerging diseases, 67(6), pp.2408-2422.

| The content of the articles are accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge. It is not meant to substitute for diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, prescription, or formal and individualized advice from a veterinary medical professional. Animals exhibiting signs and symptoms of distress should be seen by a veterinarian immediately. |

Be the first to comment